Scottie Pippen didn’t deliver his words with malice. They weren’t meant to provoke headlines or stir controversy. But they landed with weight—because they were true.

“A lot of Americans have lost jobs because we haven’t mastered the advantage of shooting the ball like our European counterparts,” Pippen shared.

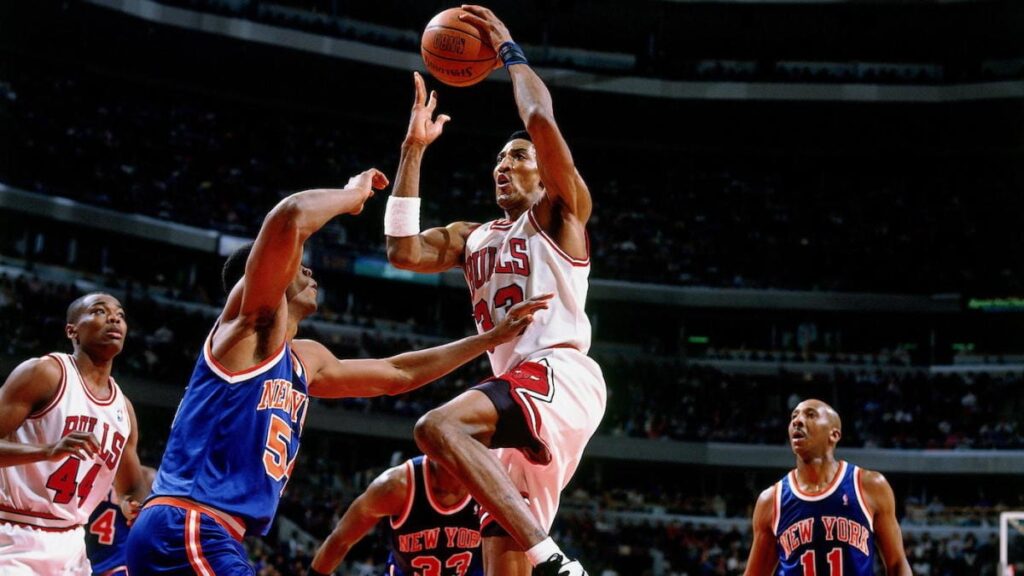

The six-time NBA champion and Hall of Famer, who helped define the golden era of 1990s basketball with the Chicago Bulls, spoke plainly about a growing concern that’s become hard to ignore: the globalization of basketball hasn’t just expanded the game—it’s exposed some of America’s blind spots.

In the 90s, American basketball was dominated by explosive athletes, isolation scorers, and defensive enforcers. The midrange was sacred, the paint was a battlefield, and jump shooting—while important—wasn’t yet the currency of survival. Fast forward to today’s NBA, and the archetype of a successful player looks drastically different: shoot-or-sit. If you can’t space the floor, you’re a liability.

Pippen’s comment speaks to this evolution—and a reckoning. Players like Luka Dončić, Nikola Jokić, and even a rookie Victor Wembanyama have entered the league with polished shooting strokes, elite decision-making, and advanced understanding of spacing and rhythm. These aren’t just talented individuals—they represent an international system that has prioritized shooting and IQ from a young age.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., youth basketball culture has too often leaned into flash: mixtape handles, viral dunks, and one-on-one highlights. The result? Players who can jump out of the gym but can’t consistently knock down an open three. In a league that increasingly values floor spacing and ball movement, that’s become a disqualifier.

Pippen’s statement doesn’t just speak to the rise of the international game—it exposes a fundamental shift in the way basketball talent is evaluated, developed, and ultimately employed. Today, skill outweighs style, and spacing beats strength. This change has tilted the balance of power toward players and programs that have made shooting a science rather than a side dish.

The data backs Pippen up. Over the past five seasons, nearly every NBA team has ranked in the top-15 all-time in three-point attempts. Offenses are designed around gravity—the unseen force that shooters exert to pull defenders out of the paint. The game has gone global, but more importantly, it’s gone perimeter. And international players, often raised on FIBA spacing and coached in shooting-first environments, have adapted faster.

To understand Pippen’s frustration, one has to consider his legacy. As the ultimate Swiss Army knife, Pippen could defend all five positions, handle the ball, and run the offense when Michael Jordan stepped away. He didn’t need to shoot seven threes a game to dominate. But in today’s game, even a player like Pippen would have been expected to stretch the floor more consistently. His greatness was predicated on versatility. Now, versatility starts with a jumper.

And that’s the core of the issue: American players have historically been taught that athleticism would be enough. For decades, it was. But that era has passed. The NBA is no longer a strictly American league—it’s a global showcase. Teams draft internationally without hesitation, and the MVP race is routinely dominated by non-American talent with polished, modern skillsets.

The NBA’s last four names who have won the NBA’s MVP award: Giannis Antetokounmpo, Nikola Jokić, Joel Embiid and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander—are all international players. Each of them brings a mix of size, finesse, and shooting touch that once felt uncommon in the States. Now, it’s becoming the standard. And with stars like Shai Gilgeous-Alexander (Canada), Josh Giddey (Australia) and Victor Wembanyama (France), the pipeline isn’t slowing down.

Pippen’s words also echo what many NBA scouts have been quietly saying for years: international systems produce more team-oriented, fundamentally sound players. From Serbia to Spain, kids are drilled on footwork, pick-and-roll reads, and catch-and-shoot mechanics before they ever dunk a basketball. In America, the reverse often happens—flash comes before function.

There’s also a structural difference. European prospects often develop in professional clubs with adult teammates and coaches from the age of 14. That environment prioritizes results and repeatable habits. In contrast, U.S. prospects are often caught between high school ball, AAU tournaments, and college systems that vary wildly in style and quality. The consistency just isn’t there.

None of this is to suggest that the U.S. lacks talent. The league is still full of elite American-born stars—Stephen Curry revolutionized the three-point shot, and Jayson Tatum, Devin Booker, and Anthony Edwards continue to evolve their offensive arsenals. But the warning is real: if a player can’t shoot, he can’t stick. There are too many Luka Dončićs and Franz Wagners ready to take his spot.

Pippen’s quote also touches a nerve that many in the basketball community have felt but not verbalized: the idea that American-born players, once guaranteed league spots on potential and pedigree, now have to re-earn those jobs on skill alone. That meritocratic shift isn’t anti-American—it’s pro-basketball. The best shooters, thinkers, and decision-makers will thrive, regardless of passport.

In the end, Pippen’s words are less a complaint than a call to action. They challenge American basketball to look in the mirror. To evolve. To re-embrace the fundamentals that once set it apart. Because if the U.S. wants to remain the heart of basketball, it has to master the mind—and the mechanics—of the modern game.

And it all starts with the shot.